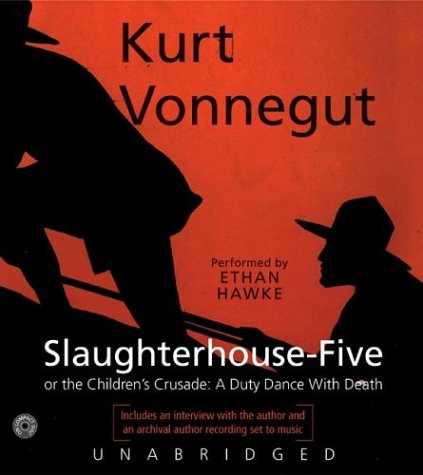

Slaughterhouse-Five

In Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. tells the semi autobiographical story of Billy Pilgrim, a man who has come unstuck in time.

Much of Billy’s time is spent during World War II. As an new soldier, Billy is sent to the front, where he is captured at the Battle of the Bulge by the Germans, and sent to Dresden as a P.O.W. Billy is not prepared for war, had just gotten through his training when his father died. He was furloughed home for the funeral, and is sent to the front so quickly after his return that he is wearing dress shoes in combat. Because he travels through time, he understands that he is helpless to change anything, helpless to save anyone, helpless to even control his own time travel. But he has been through all of this before, so he knows who will live and who will die.

The P.O.W.s are kept in a deserted Slaughterhouse, from which they witness the fire bombing of Dresden, a horrific attack on civilians that left tens of thousands dead and decimated a city. This is the pivotal moment in Billy’s (and Vonnegut’s, as he was indeed imprisoned in Slaughterhouse-Five during the bombing of Dresden) life, one that he returns to over and over again, one that flavors the timbre of this anti-war story. When Billy returns to the U.S., he wants to write a book about the bombing, about the everyday people who died, about what he witnessed. He goes to the house of a fellow soldier to discuss the book, and his friend’s wife can barely contain her contempt and disgust at the prospect. Billy doesn’t understand her hostility, until he realizes that she believes they mean to write a book glorifying war, one that will continue the cycle of violence. When she discovers that Billy wants nothing of the kind, that he wants to write an anti-war book, one that tells about how children (such young men!) are sent into battle to die, she warms to him, as do we.

Later in his life, Billy’s daughter worries that he is going insane, and that he will humiliate the family, because he talks openly about his experiences on the planet of Tralfamadore, where he was taken and put in a zoo, where he lived for several years in an exhibit on the reproduction of humans, where he makes love with a beautiful (thankfully human) adult movie star while the Tralfamadorians watch. He is, of course, never missed on Earth, because he is returned at the very moment that he leaves. From the Tralfamadorians he learns that not all beings experience time the way that we do. Not even the way that Billy, unstuck as he is, does. For the Tralfamadorians, all time exists at once, all that was or is or will be, they all exist side by side. From them he also learns the Tralfamadorian saying, “So it goes”. They are not disturbed to see a tragedy, because they are able to see the entire before and after of that tragedy, so they understand that when someone is killed, that is but a moment in their time, and all that has come before is still every bit as real as the fact of their death.

I very much enjoyed Slaughterhouse-Five. I’m not sure how I missed reading it in High School. Perhaps I was too busy reading the short stories of James Joyce (which I adored), or being taught speed-reading (I know, right?).

4 Comments

Starshine

You can actually be taught how to speed read? Wow! Never knew that! Brian reads very speedily and I read average, I guess. It doesn’t make reading a book “together” very enticing, though, because he is always finished long before I am.

Happy Thanksgiving!

J

Starshine, this was more like that ‘Evelyn Woods Speed Reading’ that they used to show ads for on TV. Skimming, really. Nothing whatsoever to do with English, just trying to make getting through books easier on the kids who hated reading, I guess. The teacher was nice, but it was a real waste of time.

OmbudsBen

This book, and Vonnegut’s “Breakfast of Champions” had a very big influence on me when I read them as a teenager. I’m really glad you liked “Schlachthaus funf” (what he’s taught to say); the movie is okay, too (if you can find it) and it does justice to the book (in its own context) but the book is wonderful.

About speed reading — half a century ago self-improvement programs like this were quite popular. And yes, there were classes to try and teach it. Plus people who were freakishly fast. So in one instance I know of, they would have someone stand on stage, open a new book and flip through it, then be able to answer questions. As I say–freakish. The truth is, you can learn techniques to improve how you assimilate information, but most of us could no more read that fast than we could hit home runs as often as Barry Bonds did.

Dad Who Writes

This was a book I wrote about in my BA dissertation so many years ago! I must go back and dig it out again. I was deeply moved by it at the time.

Reading – I’ve always been a pretty fast reader but I do find that as I get older, I’m consciously slowing down. I suppose I’ve got different motivations for reading no. Apart from corporate policy documents.