A Tale In Three Parts

I didn’t grow up in what you might call a ‘traditional’ family. My mother raised my brother and me by herself, and we had no contact at all with our fathers or their families. When I was 21, my mom got in touch with my dad, and he came to California to meet me. That was almost 19 years ago, and we’ve had a pretty good relationship ever since. I will never have the childhood that I would have had if they had stayed in contact with one another, but the childhood I did have was a good one, mostly happy and secure in the love of my mother.

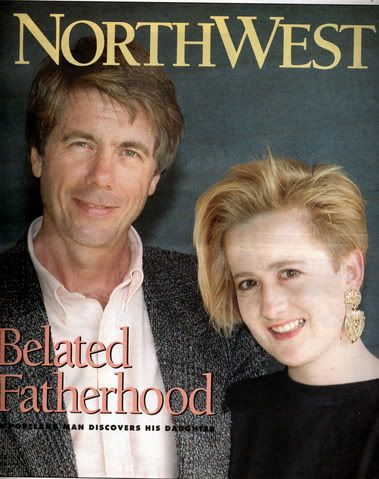

A few years after meeting my dad, a good friend of his, Susan Stanley, who is a freelance writer in Portland, OR, asked if she could write a feature for the newspaper there, the Oregonian. We all agreed, and she interviewed us; Ted’s step dad (he’s a photographer as well as a graphic artist) took some pictures, and our story was published in the Oregonian’s Sunday supplement, “NorthWest”, on July 15 of 1990.

I’ve thought a lot since starting my blog about telling this part of my story, but it’s huge and daunting, and I don’t want to get it wrong. Well, last night I was looking through some old boxes, and I found a copy of that “NorthWest” supplement. I thought, that’s it. I’ll post that. I thought of scanning it, but it’s too big and doesn’t fit well, and would be hard on your eyes as a jpeg. I looked on the Oregonian website, but they don’t seem to have stuff that old archived. So, I’m typing it. Geez, the things I do for you people. However, it’s really long. The author was writing for a supplement, so there’s a LOT of detail, and maybe our whole names are used about 100 times when a first or last name might have worked better sometimes. But it’s a good telling, interesting in its 3rd person point of view, etc. Because it’s so long, I’m going to break it down into two or three posts. 1st is the intro, and my dad’s side of the story. 2nd will be my mom’s side, and if that is looking pretty long, I’ll put my side as part 3. If mom’s is shorter, maybe I’ll put my side in part 2 as well. My dad gets the most press here, because she’s his friend, and it’s a story of ‘belated fatherhood’, not ‘belated daughterhood’ or whatever you might want to call it. 😉 Here goes.

Belated Fatherhood

by Susan Stanley

One rainy October Morning in 1987, around 8 or so, Michael Wells was stumbling around the kitchen of his Northwest Portland apartment, trying to put together a cup of coffee, when the phone rang.

briiing!

“Hello?”

“Is this Michael Wells?”

“Yeah” (Coffee, coffee, where is that coffee?)

“Hello, this is Joycelyn Ward”

Joycelyn Ward. Joycelyn Ward? This can’t be the Joycelyn Ward from 20, 30 years ago, Wells says to himself. Not the Joycelyn Ward he went to high school with back in Modesto, California.

But it is. Wells and Joycelyn Ward exchange pleasantries. Then she tells him the reason for her call.

“Michael, I’ve done a terrible, terrible thing. I’ve kept you from getting to know Julie.”

Suddenly coffee was forgotten. Wells sat down. Oh, God. It was true, then. Michael Wells had a third daughter. He knew Joycelyn had a daughter named Julie, and there’s been a lingering suspicion that she might be his, the result of a one-thing-leads-to-another evening in 1965. But the revelation was stunning.

“Would you like to, you know, talk to her?” Ward asked. “Would you like to meet her?” There was no obligation, she insisted. He could pretend the phone call never happened.

No, no, Wells assured her, he did want to meet Julie. But give him a little time to think about it. To come up with what to tell his other kids. To digest what he had just heard.

Wells may have been shaken, but he was neither ashamed nor scared. Sure, he’d grown up in the “happily ever after” decade of the ’50s, when the notion of family was defined by wedded bliss and three-seater station wagons. But he came of age in the ’60s, an era that emphasized voyages of self-discovery instead of togetherness. When he and the others of his generation left home for college or the war, they often returned with a different way of looking at the world.

Their new way of looking shook the traditional family structure to its roots. New structures were put together, jerry-built from the wreckage. Notions of ‘family’ took on new forms. Single parents. Childless couples. Two-income couples. Joint custody of children. One-parent families.

In light of these developments, Michael Wells, Joycelyn Ward and Julie Ward also are a family. Not the kind that kissed one another good night, or bickered over bowls of cereal, or opened presents together on Christmas morning. Still, their story is one that, ironically, reaffirms the value of family ties, those connections both emotional and genetic. In it, a father solves a mystery and comes face to face with the legacy of his past. A mother stares down her past, finally grasping how her ruined childhood has leaked into the present, indelibly staining her own children even as she sought to shelter them. And, most important, a daughter finds the father she’s dreamed about, in order to start building the relationship she’s yearned for.

Michael Wells:

Becoming the Father

“How many kids do you have?” A man is often asked. “Two – that I know of,” goes the lame joke. Or one, or none, or whatever.

Paternity’s Twilight Zone. Like many men, Michael Wells knows others who suspect they have kids they’ve never met, faceless progeny they seldom think about.

For most of these men, it’s a fearsome thought. A belated birth announcement often arrives firmly stapled to a back-and-future-child-support bill. But for Wells, the phone call confirming his daughter’s existence was welcome. At the very least, it solved a long-lasting mystery. The caller, after all, was a woman he’d known and trusted for some 30 years, even though they’d been out of touch most of that time. And as a parent, Wells welcomed the responsibility long before participatory fatherhood became fashionable. When his marriage of 13 years ended in 1979, he insisted on joint custody of his daughters, Maya and Melissa Wells. More than most fathers, he cooked for them, helped them with their homework, monitored their social lives.

The role fit Wells’ politics and perspective. Long the kind to work up a sweat for liberal causes, he’d traipsed door-to-door and pounded signs in the grass during more election seasons than he’d care to remember. California-reared, a Berkeley dropout, Wells worked for civil rights in Georgia and did stage lighting for the proto-Yippie New York underground rock group The Fugs. His organ-donor card had been witnessed and signed by beatnik poet Allen Ginsberg, no less. Formerly a Quaker since the mid-70s, he’d been too “politically pure” to apply for conscientious objector status. But he’d espoused non-violent, life-affirming values since his teens.

When Joycelyn Ward called him that October day in 1987, Wells had left behind a string of jobs – among them starting and working for Portland’s alternative press and serving as development director for the Oregon chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union – to train himself to write grant proposals for non-profit organizations. He was living on savings and a small inheritance. And, having just emerged from a years-long live-in relationship, he was in what he calls an “avoidance mode,” dodging romantic entanglements.

Wells, now 46, first met Joyce Ward in high school geometry class. The year was 1958; he was a sophomore and she a junior at Thomas Downey High School in Modesto. Wells remembers Mr. Higgs as a good teacher, because he’d let you work out the answers however you got there, not just by memorizing the formulas and parroting them back. Ward, Wells – seated alphabetically the way they used to do things back when the former Army general named Eisenhower was looking after the country. The girls, their breasts scooped into pyramidlike cones, wore pleated plaid skirts, little detachable white collars tucked into the necklines of their sweater sets. If their hair would cooperate, they combed it into duck tails, or slept every night on rollers, the better to coax their tresses into a pageboy, or to bend the ends up into The Flip. The boys wore ironed shirts and Levis and neat hair – in Wells’ case the haircut called a “Brutus,” short and combed down.

With her short cropped red hair and funny 50’s glasses, Joyce, like Michael, enjoyed her reputation as one of the school’s eccentrics. Wells was on the track team his junior and senior years; so he had his jock friends. And his parents were conventional types – his father worked for a company that made turkey feed, his mother serving as Modesto’s Welcome Wagon lady. But Wells liked to hang out with the beatnik set.

On a Bay Area visit during his senior year, Michael Wells fell in love with early-60’s Berkeley, with its intellectual ferment and clamorous bull sessions and “bookstores that weren’t Hallmark card shops.”

That fall of 1961, Wells discovered that his Berkeley classes were just as dull as high school, that the eagerly anticipated “great intellectual discussions” took place outside the classroom. And that his instructors were 28-year-old grad students with no teaching experience, committed to the university’s publicly acknowledged goal of driving out half of each entering class to create a “manageable” student population.

Wells dropped out of Berkeley and “started living the bohemian life, traveling back and forth to the East Coast.” In the spring of 1965, having just been convicted of draft resistance and on his way to the East Coast, Wells stopped in Sacramento (J’s note: it was San Francisco, not Sacramento) to visit Joycelyn Ward, who was separated from her husband. It was, as he describes that period, “certainly the most promiscuous time of my life.”

“I was coming to say goodbye…and we ended up in bed,” he recalls. Moving on to do alternative service at Goodwill Industries in Boston, he later heard that Ward was pregnant. But “I assumed, as she apparently assumed, that it was her husband’s kid, and went on with my own life.” That summer, Wells met the young woman he would marry.

As he remembers it, Julie was about 2 when Joycelyn Ward wrote to tell him that a mutual high school friend, on seeing the toddler for the first time, suggested the child should’ve been named “Michelle.” Even then, Wells says, it didn’t sink in, a fact that strikes him now as typically male for those times. (J’s note: This is sometimes how my parents communicate…my mom thought that was enough, and she had communicated the news to him…he didn’t catch on…neither one carried the conversation any further….strange to me…) Maya and Melissa Wells were born in 1970.

Early on with his twin daughters, Michael Wells’ experience of fatherhood was, he says, overwhelmingly positive, “probably the central most wonderful thing in my life…yeah, just wonderful.”

After his marriage ended, Wells created a sprawling household in a tall, Northwest Portland Victorian with a woman who had partial custody of her twin sons and daughter. The twosome, which at times expanded to seven counting Wells’ daughters, continued for six or seven years. Then the pair split.

Wells spent the next few years focusing on his daughters, “realizing,” he says, “that through really no fault of their own, my twins had just gone through two family breakups.”

Briiiing! That phone call chimed at the start of Wells’ second year of self-imposed monkhood. Yes, he would be interested in meeting his daughter. But give him some time, OK?

Soon after that fateful phone call, Joycelyn Ward wrote Wells a letter, cramming the envelope full of baby pictures of his daughter, now 22 (J’s note…I was 21) and working her way through San Francisco State University. (“Which you could say wasn’t playing fair,” Joycelyn says, “but it was, on the other hand, full disclosure…”)

Wells decided the first contact between father and daughter shouldn’t be over the telephone, “this disembodied voice of somebody you’ve never seen.” He told Ward he’d like to come down to see the two of them. He said nothing to his younger daughters.

Once Wells got to Stockton, he and Ward re-established the rapport of their high school days. The two made plans to drive to San Francisco the following day to visit their daughter.

“I was, of course, absolutely terrified,” Michael Wells admits. “Terrified that this child was going to feel abandoned, was going to hate me. I mean, here’s the father who never showed up, you know?” What-what?-could he say to her? Driving to San Francisco, his palms sweated, his mouth went dry again. Joycelyn, chattering away, assured him they’d get along fine.

The pair arrived in San Francisco, at Julie’s apartment.

Briiing! goes the doorbell.

A young woman comes to the door.

“This is your father,” Joycelyn Ward tells the daughter.

“This is your daughter,” she tells the father.

Tomorrow: Part II

One Comment

Pingback: